Disastrous Camouflaging & Other Acts of Sabotage

My obsession with order, color-coded tables, and detailed plans is likely related to autism. Unsurprisingly, one of the first things I did when planning this newsletter was create an editorial calendar with publishing dates, preset topics, notes, and links to useful resources. Everything neatly categorized, with rows and columns in different colors, of course. So satisfying.

According to my schedule, today I was supposed to write about diagnosis. However, a few things have happened over the past two weeks that I think are worth reflecting on. Partly for myself – to process everything, because this newsletter is also a space for me to make sense of my often chaotic everyday life. But mostly, to share reflections that I hope might help someone else out there feel a little less alone in this overwhelmingly neurotypical world.

On activism & friendship

In the city where I live, Saturday, the 14th, was Pride. This year, with open hostility against the queer community on the rise, showing up felt more urgent than ever. Plus, I and my Palestinian flag both felt the need to reiterate that there's no Pride in genocide.

Right after the march, I had plans to attend another Palestine-focused event. There would be live music, and one of my dearest friends was performing. Skipping it was not an option.

Since learning I’m autistic, I’ve been working hard on managing my energy levels when it comes to highly social, overstimulating settings. Before understanding how my brain is wired, I used to chalk my lack of stamina in these situations up to being “just introverted.” And I constantly blamed myself for not being able to “do normal things and have fun like everyone else.” I had no idea there was a clear explanation for all of it.

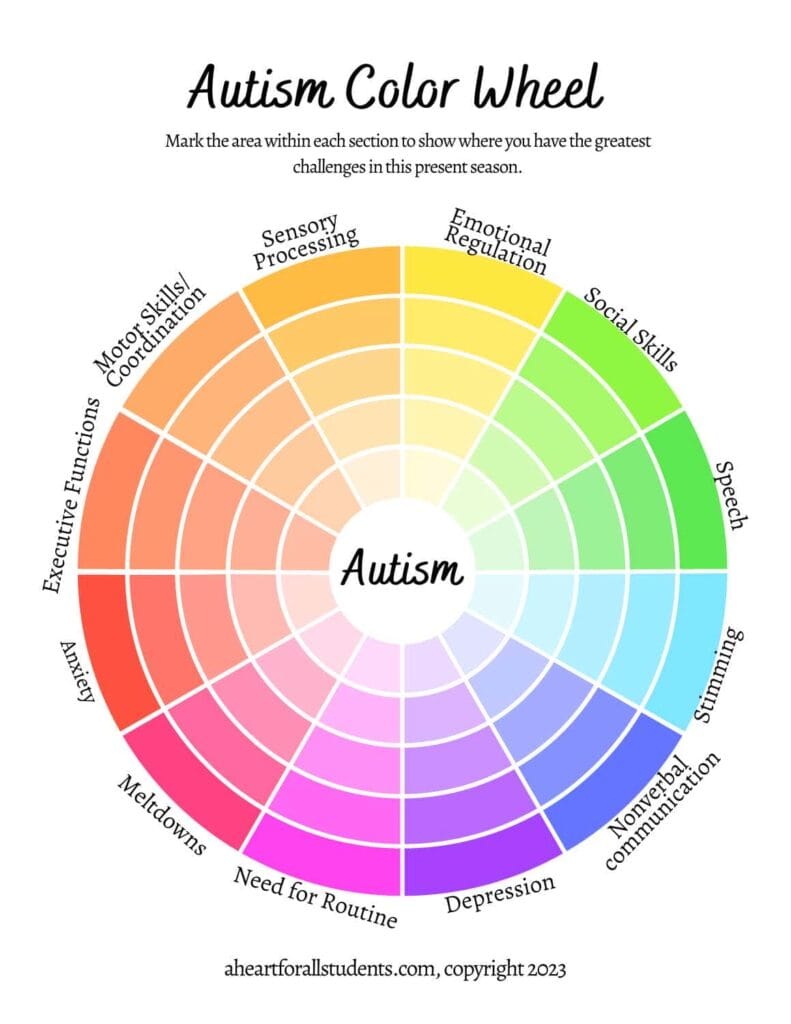

Autism used to be visualized as a straight line, with “high functioning” on one end and “low functioning” on the other. This kind of categorization is arbitrary and deeply pathologizing – high or low according to what? Capitalist, ableist, neurotypical productivity standards? It reduces a deeply diverse lived reality to two narrow and dehumanizing archetypes: the eccentric genius or the non-verbal disabled man. And yes, I’m using the masculine form intentionally.

Thankfully, in recent years, that linear model has been replaced by a circle – something like a pie chart where each slice represents an area where an autistic person may face more or fewer difficulties. It’s a much more accurate way to reflect the infinite variety of autistic experiences, including not just points of tension but also strengths.

I haven’t yet mapped out my own personal version of the diagram, but I do know I struggle moderately with social interaction and managing auditory stimuli. I usually do okay in one-on-one interactions, even with strangers, or in small groups. But in crowded settings – or large, noisy groups where people are chatting and dancing and celebrating – I turn into a piece of wood soaked in anxiety. I’ve never understood how it’s supposed to work, and I probably never will. I don’t know what to do, what to say, how to behave. Even just figuring out where to be in a room becomes a challenge. Add a few decibels to that, and my brain short-circuits.

For some reason, I’ve always loved attending live music events. But if the context is different, loud noises – especially the chaotic, continuous chatter of a large crowd – can become deeply overwhelming.

And so, back to Saturday. I knew it would be hard on me. But I didn’t want to back out – not as an activist, and definitely not as a friend. With a lot of mental prep, some advance rest, and my life-saving noise-cancelling earplugs, I made my way.

Guilt & co.

The crash came, as expected. Being at Pride, surrounded by my friends’ love and waving a Palestinian flag, filled me with joy. But after three long hours in a sweaty, noisy crowd, my nerves were fried. On the walk to the venue where my friend was performing, I had a small breakdown. I had to sit on the curb for a while to calm myself down. I was exhausted, my mind foggy, unable to string two thoughts together or even decide which way to walk.

When I finally got to the venue, the worst of the crash had passed, but I was still in a full-blown sensory shutdown: disconnected from my surroundings and not up for any kind of interaction. Slumped in a corner, I tried to gather the minimum energy needed to at least enjoy my friend’s performance. Throughout the evening, a few people approached me to ask if I was angry or sad. I really wished I had a sticker on my forehead that just said AUTISTIC – maybe it would’ve saved me the effort of those strained, reassuring smiles. As soon as my friend's performance was over, I gave her a hug and pretty much fled the scene.

The next day was tough. I spent most of it in bed, half-asleep. On top of the brain fog, dizziness, and mood swings, my body just wouldn’t cooperate. I only managed to drag myself to the kitchen for something to eat late in the evening, and I had to miss a Palestine solidarity march I had really been looking forward to.

I’m writing this two days after Pride. I feel better, but I’m still recovering. Over the past couple of days, I’ve caught myself wondering what my life would be like if I weren’t neurodivergent. Maybe I would’ve enjoyed Pride without a second thought. Maybe I would’ve had enough energy to attend the Palestine event and celebrate my friend’s brilliant set. Maybe the next day, I’d have gone to the march feeling recharged and ready.

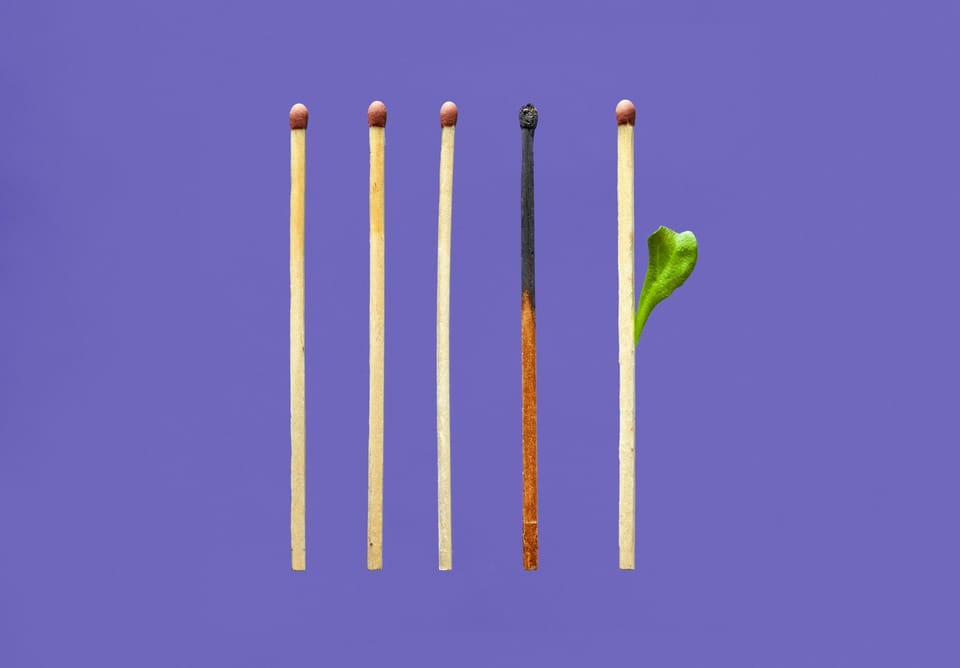

I’ll never know – but these thoughts often creep into the folds of my most tired days. I ask myself whether I’m enough – as a friend, as an activist, as a person. I wonder if these constant roadblocks are insurmountable obstacles on the path to becoming the human I want to be. Sometimes it feels like there’s an unbridgeable gap between my inner world – what I feel, what I believe in, my values, the way I perceive myself and everything around me – and the outside. Like I just can’t translate who I am and what I really want in a way that others can grasp.

In The Autists: Women on the Spectrum, Clara Tornvall writes:

“Autistic people rely on themselves and are very resistant to groupthink. In contrast, they often find it baffling how neurotypicals care so much about what others think of them. They often have a strong sense of justice. Their stubbornness and capacity to focus on a specific interest mean they never give up. And these are excellent traits for an activist.”

Lately, I find myself coming back to this quote, especially when it feels like I’m failing again and again to live up to my own expectations. It reminds me that the uniqueness of my brain plays a vital role in making me who I am. And that many of the struggles I face are amplified – or even created entirely – by a system that measures our worth through standards of conformity and relentless productivity.

Small revolutionary acts

We are all living under the crushing pressure of performance. In every area of life, the imperative is to shine and smile, always. To play along, to never stop, to be constantly ready and proactive. Even in our relationships, we’re often led to believe that quantity trumps quality. Hyperconnection and constant interaction have become the markers of “normal” social functioning. Falling behind can easily result in a gnawing sense of inadequacy, leading to chronic anxiety and depression. I speak from experience.

The more I learn to understand and accept my autism, the more I see its subversive potential. I don’t want to romanticize anything – being neurodivergent can be incredibly exhausting. But within the limits and lived experiences of each of us, I’d like to invite you to try shifting perspective.

In a world that moves too fast, we ask for slowness.

In a world that demands constant connection, we try to unplug.

In a world that’s too loud, we ask to turn the volume down.

It’s a continuous act of reclaiming space. A daily practice of sabotage that refuses and rewrites the rules set by the majority.

I like to think of my autism as a crowbar prying open the locks of this system and shaking its foundations. Perhaps we neurodivergent folks hold the key to something new. If we started occupying all the space we deserve – in our own ways, and without compromise – maybe the world would have to adapt to our slowness, our different needs, our zig-zag thought patterns. Maybe it would start to look like a more liveable place. A better place, not just for us, but for everyone – a place where faking a smile when someone asks “how are you?” is no longer a requirement.

Clara Tornvall – The Autists: Women on the Spectrum

Clara Tornvall is a Swedish cultural journalist and producer. In this book, she shares her experience as an autistic woman who was diagnosed at age 42. Weaving together personal narrative, interviews with other autistic women, and interludes focused on history and data, Tornvall creates a story that challenges the outdated stereotypes surrounding autism. It’s a deeply insightful book that kept me company and brought comfort during the harder days.

Thank you for sticking with me until the end.

If you feel like it, you can share your thoughts by replying to this email or leaving a comment.

Talk to you soon,

Camilla

🪼 Sommersə is free by nature, and it always will be. I deeply believe in accessibility and the free sharing of knowledge.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please help me grow the project by spreading the word.

If you're in a position to do so, you can support my work with a donation on Ko-fi. Every contribution helps me keep this space alive, free, and independent.

Member discussion